LIFE OF OHARU (ENG)

Mizoguchi Kenji, 1952

I see when men love women. They give them but a little of their lives.

But women when they love they give everything.

Every woman is a rebel, and usually in wild revolt against herself.

-Oscar Wilde.

The end of this paper it to analyze the film The life of Oharu -directed by the japanese director Mizoguchi Kenji and premiered in 1952- from an academic perspective and film studies. Therefore, the main question before us would be the one that follows: What is Mizoguchi wanting to say in this film? How does he manage to do so? What are the film techniques that he practices in The life of Oharu; the particular film language that he develops? In order to give an appropriate answer to this questions I will analyze the main themes, characters and issues present in Mizoguchi’s film and, while doing so, I will describe the specific resources and film techniques that he uses for this purpose.

First of all, as with any kind of art, it is imperative to have some knowledge about the historical context in which the movie was filmed. When studying a particular work of art, even a cursory consideration about its background is a huge assistance. The Life of Oharu is based on various stories from Ihara Saikaku's The Life of an Amorous Woman. Despite being under-financed, the film was one of Mizoguchi’s favourite projects, since it was greatly influenced by his personal life. The movie was a way for the director to remember his sister, Suzo, who raised him and, just like Oharu, was also sold by his father as a geisha. From this few historical facts, we might glimpse some of the main issues of the film: the fragile situation of women in Japan, and the importance of memory. Had Mizoguchi’s Japan truly changed since the times of Oharu? Is it any different for Japanese women?

The life of Oharu tells the story of a woman who tries her best to find love and ends up trying even better to just live. The film starts with a long take of the heroine, Oharu, as she walks the streets looking for clients. She is old and covers her face with a veil. It is noticeable the contrast between Oharu (alone, old, covered) and a young prostitute having a successful night (she is uncovered and accompanied). After this scene we witness how she joins a group of other old prostitutes and they all take refuge on a fire set on the streets. Oharu is an old prostitute (more than 50 years old) who makes her life out of walking the streets, with her face white-painted, trying to seduce anyone who would take her. The harsh conditions of her life are remarked by her own words, "It's hard for a 50-year-old women to pass as 20." After hearing the chantings of the monks from the fire, Oharu goes to the temple as if she was answering a call. When the shot ends, a new travelling takes its place and it seems almost as if the temple goes to greet Oharu.

In this temple, the film’s heroine finds herself surrounded by statues of the Buddha. It is almost ironic that, in Japanese Buddhism, this proliferation of Buddha statues in one place almost always refers to the “thousand faces of the Buddha”, which, at the same time, refers to the compassionate sight of the Japanese bodhisattva Kannon: the Buddha sees us all in our individuality, in our own particular character. And yet the sequence -recorded from a mid-shot and with no close-ups for us to see deeper into Oharu’s face, nor into her emotions- could not be more cold and impersonal. For there has never been any compassion towards Oharu. Is Mizoguchi turning around the meaning of the Buddhist images? This coolness is reinforced by the monotonal chanting of the monks and by Oharu’s herself (hidden as she is behind a dense white makeup). Is not this old and face-painted Oharu the embodiment of all the suffering women of Japan? Whatever the case, the following shots breaks the previous feeling of quietness. Alternating high-angle shots of Oharu with low-angle shot of one particular Buddha among all others, we receive an image of Oharu’s own perception, and with it, her curiosity and, maybe, her wonder. For she has recognized on the Buddha statue the image of Katsunosuke, her former first love. Overlapping the fading image of the statue with that of Katsunosuke, Mizoguchi takes us to the beginning of the story; to the day on which Oharu’s life change forever.

I. Love, Pride & Suffering

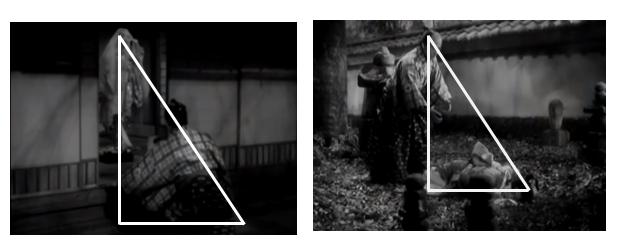

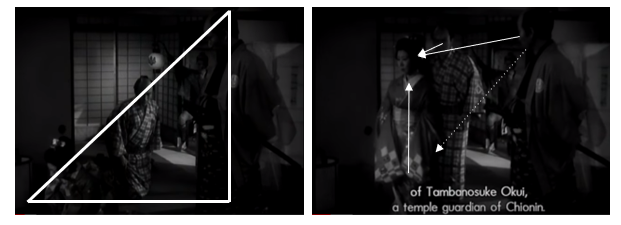

The life of Oharu goes -in a demeaning and slow movement- from her privilege position as a lady in waiting at the court to the wandering life of a begging buddhist nun. However, we can see some of her former pride in various moments of the movie. Due to the lack of close shots in the film, this pride is not show in a “moral” way, on the contrary, the predominance of mid-shots puts pride on a different status. It is almost as if we were watching a documentary film in which pride, love and suffering are shown from a more socially-focused perspective. Indeed, throughout the whole movie, Mizoguchi forms most of its sequences through triangular power-relation images. At the beginning of the story, when Katsunosuke is declaring his love for Oharu, we see him on his knees outside the house while Oharu is proudly standing up inside (as if Katsunosuke was asking for “entering” into Oharu’s heart). However, when she finally surrenders to him, the composition of the image changes completely and now is Oharu the one on the ground while Katsunosuke is standing up (victorious).

Just a few minutes later, a third figure interrupts the lovers and, in the same way, the distribution of the characters in the picture reveals the relationship between them: the newcomer, some kind of samurai, is standing completely straight, while Katsunosuke interpose himself half-raised on his knees between Oharu and the samurai. When the late occuses Oharu of being a prostitute, she raises in all her pride and reveals her high social position, leading to the subsequent disaster: the death of his lover and the exile of Oharu and her entire family. Love, pride and suffering are all shown intertwined on the scene and sketched out in the image.

Despite the fact that this late composition, in which Oharu is on her knees subjected to the power of others, is repeated over and over again in the movie, there are a few crucial shots in which Oharu’s hubris raises. However the case, they all end the same way: destroying the relative peace that she had managed to find and leading to an deeper suffering. Just a few quick examples are the scenes in the nun’s monastery, in which Oharu has manage at last to find some peace (if not love), a peace that will only last until the silk merchant calls her a whore, when she arrogantly takes off her kimono and throws it to him. A few minutes later, the nun that had offered Oharu shelter discovers the clothes left on the floor and banish Oharu from the monastery. Although the ambiguity of the shot (the nun looking at the clothes as a shadow runs behind a folding screen), the consequences are the all the same: it does not matter how many doubts might be around a woman’s actions, society will always think the worse ("Caesar's wife must be above suspicion."). Another more brief example would be the sequence in which Oharu refuses (standing up) to lower herself when a rude countryman tries to buy her with his gold like he had just bought everything else at the House of Geishas, and the owner of the house threaten her never employ her again (at this moment, she throws her to the owners feet). From the perspective of cinematographic montage, this recurrent up and down in both the actual life of Oharu and in the images of the film brilliantly reflect Oharu’s struggle against misfortune.

Example one:

Example two:

II. It is a man’s world

Introduced in the previous theme, Mizoguchi’s idea of the Japanese society is, in words of the french philosopher Gilles Deleuze, “both simple and extremely powerful: for him (Mizoguchi) there is no line of the universe which does not pass through women, or even which does not issue from them; and yet the social system reduces women to a state of oppression, often to disguised or over prostitution. The lines of the universe are feminine, but the social state is prostitutional. Threaten to the core, how could they survive, continue or even extract themselves?”

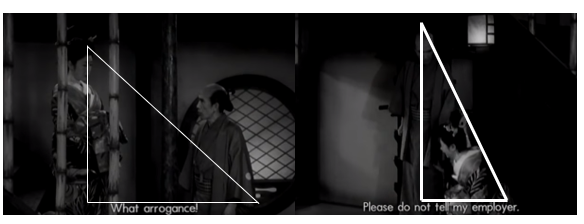

The term “gynoecium” perfectly describes Mizoguchi’s conception of human cosmos: the world saw as both an immense flower (first sense of the word that refers to the parts of a flower that produce ovules and ultimately develop into the fruit and seeds) and a vast prison for women controlled by men (second -an original- sense of the term, via Greek γυναικειον or gynaecēum, from γυνη-gynē, feminine, and οἶκος-oikos, house). Through the cinematic montage, Mizoguchi shows us the futile efforts of Oharu (and with her, of all women in Japan), who has been trapped since the beginning of the film in a world rule by men. The images resembling cages and cells are also recurrent. A beautiful prison indeed, but a prison nonetheless. “The life of Oharu is the fate in microcosm of many Japanese women for centuries, in a society ruled by a male hierarchy”.

III. The rolls of women in Japanese society.

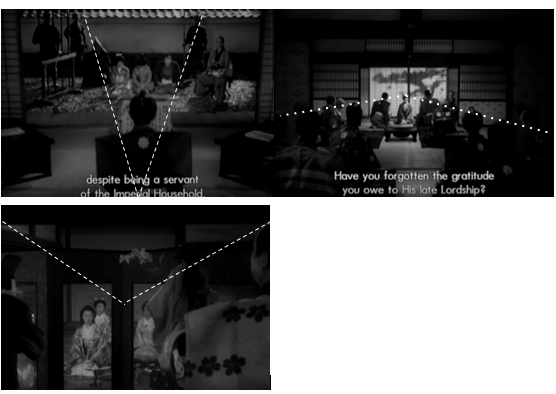

As if been born on a prison was not enough, Mizoguchi ironically reflects on the screen how unfair Japanese society is for women. For not only they are confined by countless senseless rules but, as it has been advanced with the first theme analyzed on this paper, there is no fair trial for those who are suspected of having broken them. Oharu’s endless circle of misfortunes begins with a mockery of a trial that Mizoguchi portraits almost as a theater play (since the sentence has been decided before the trail ever began). In fact, the movie’s ending starts with another trial -as spurious as the first one- in which men take Oharu away of her last hope: her son. In Deleuze words: “the line of the universe which goes from mother to son is irrevocably barred by the guards who separate the unfortunate woman from the young prince whom she brought into the world.” The theatricality of the trials is remarked by the actual play that takes place at Lord Matsudaira’s House in the middle of the story in a rather Shakespearean way. Indeed, Mizoguchi uses a similar image-composition for both the trails and the doll-theater show whose story, on the other hand, reveals what is happening to Oharu at that moment of the film (as Ophelia said to Hamlet: “Belike this show imports the argument of the play.”).

Sure enough, the doll-play contains more than just the love-struggle between Oharu and the Lord’s wife, it synthesizes the whole Life of Oharu. She has been treated as a doll for her entire life: first, her father sold her as a concubine into the household of Lord Matsudaira, afterwards, when she is expelled by Matsudaira’s lieutenants for “weakening” their Lord by making him fall in love with her, Oharu’s father put her to work in a geisha’s house; but the worst despicable use of Oharu is, without a doubt, when she was taken by a buddhist pilgrim to be held up as a moral spectacle. "Look at this painted face!" he told them. "Do you still want to buy a woman?" A cruel fate, indeed, for a woman who has been treated immorally almost every day of her life, and who has always behaved as morally as it was within her power to do.

Finally, a quick note about a sequence to horrible to ignore which sums up what has been said here about this theme; a sequence that we might very well call “women for sale.” Before finding Oharu, Lord Matsudaira’s servants are desperately looking for a concubine who could both bear Matsudaira’s child and satisfy his high requirements concerning women. In the middle of the search, there is a sequence, shooted with a slow tracking shot, in which one of this servants is looking among dozens of women quickly discarding them for the tiniest “defect”. It is almost like a “shopping-mall scene” in which women are the products on sale. The slow movement of the camera heavily contrasts with the frantic activity of the characters and music, making the sequence even more stressful and unpleasant. The image of women being treated as merchandise is reinforced by Oharu’s expulsion of Matsudaira’s house once she has delivered the child requested; “she has played her part and now she is been disposed as a breeding horse.”

IV. The image on the screen: Mizoguchi’s personal philosophy

Although Mizoguchi does manage to make houses and palaces look like a women’s jail (by framing the sequences in one or more frames), the cage in which Japanese women are imprisoned is not always an actual jail. As said before, women are confined by the very world in which they were born; “this is how it was, this tiny world of women.”[1] Confined by all the rules and conventions they are taught to follow blindly since they are born. This hopeless situation is often reflected in Mizoguchi’s films: in this particular film, Oharu is not the only one who is forced to obey men (“Is this your idea of duty” -Oharu’s employer at the red district scolds her when she refuses the rude countryman), but also the highest Lady, Lord Matsudaira’s wife, has to welcome and endure her husband’s concubine (“You must endure everything for the good of the family.”). In The life of Oharu, when the irrationality of all these rules, fake trials and unfair judgments achieves its top, an emotional outburst is the only protest raised by women.

In this regard, Deleuze’s word could not be more appropriate: “she knows that the very success will shatter the line, giving her nothing but a lonely death.” Mizoguchi’s films aren’t those of big action and great heroes in which the protagonist faces a menacing world and changes it with his actions; on the contrary, Mizoguchi’s gradually creates a “tiny world of women” that you cannot recognize as a potential menace until it is revealed, not as a menace, but as inevitably hostile to his female characters. Women cannot escape the prison-world in which they were born and certainly they will not change it. The subsequent frustration is shown, as said before, through an emotional revolt: the sequence that follows Katsunosuke’s beheading, recorded using a fast tracking shot, shows us a desperate Oharu, running from her mother through the woods as she tries to commit suicide. For what is suicide but the ultimate escape-route? Oharu knows that she cannot do anything against Katsunosuke’s unfair fate, she is powerless and her actions are of no use but to show how powerless women in Japan are. At the ending of Sisters of the Gion (1936), Mizoguchi puts Oharu’s desperate efforts into words through Omocha’s final speech: “If we do our jobs well the call us immoral. So what can we do? What are we supposed to do? Why do we have to suffer like this? Why do there even have to be such things as geisha? Why the world needs such a profession? It’s so unfair. I wish they never existed! I wish they never existed!”

However, being as he is a great film director, these ideas, which conform his -almost metaphysical- conception of the world, are sustained throughout the movie by the use of particular film-techniques: by his personal film-language. Firstly, the relatively high position of the camera, which produces the effect of a high angle shot in perspective and encloses the area in a narrow space; secondly, the distance of the camera that refuses to go beyond medium shots for almost the whole movie, apparently neutralizing the scene, but actually maintaining and prolonging the emotions contained in it to its very end; finally, and most importantly, the sequence shot that works as a very roller, sometimes slow (like on “the market of women” scene), sometimes fast (like this last sequence of Oharu’s runaway), but always ravaging everything on the screen.

V. Final reflection

Thinking once again from Deleuze’s philosophy, we may stabilized a comparison between Kurosaga and Mizoguchi. Against the Japanese master of the great form (or great action), Akira Kurosawa, stands the small world of women of Kenji Mizoguchi; a world both hidden and essential, mysterious and decisive. The image-adventure, properly masculine, of The Seven Samurai is not the only form of image-action. On the contrary, in The Life of Oharu or in The Sisters of Gion, Mizoguchi needs a more subtle image; a tapestry of actions or image-weft. The particular philosophy of the Japanese filmmaker, centered on the feminine vector of the universe, does not match with the quarrelsome heroism of the image-adventure. Japanese women does not face a threat, they are submerged in the threat: in a hierarchical system against which there is no possible confrontation. Thus, in the small-form (or small action) we do not witness a fight or duel in which the protagonist opposes a threatening situation and ends up transforming it; no, in the image-weft the action progressively reveals an imposed environment uncovered by the very efforts of the female protagonist, whose actions -directed towards a new spirit and strange to the imposed system- would inevitably be consumed in her final solitude and death.